In 2013 the remains of King Richard lll were discovered under a parking lot in the city of Leicester. Despite the fact that the English king lived in the 16th century, archaeologists could confirm that he died of battle wounds and, unlike Shakespeare’s portrayal of him in the eponymous play, Richard lll’s scoliosis of the spine would probably not have made him a hunchback. They also discovered something else: the king had worms.

Parasitic worms are collectively known as helminths and include cestodes (tape worms), nematodes (roundworms) and trematodes (flukes). They come in many different shapes and sizes – from microscopic organisms to metre-long adult worms – and often have complex lifecycles. Most importantly, they have been with humankind for a very long time. Ancient Egyptian papyri mention them, Hippocrates wrote about them and, in the case of Richard lll, it is thought that he suffered from a roundworm infection as evidenced from the large number of nematode eggs found in the soil around his abdominal cavity.

Today, while rates of exposure in developed countries have fallen, at least a billion people in sub-Saharan Africa, Asia and the Americas suffer from a helminth infection. In many cases these infections cause serious health problems and death. But not in all cases. It is now known that some helminth infections can be beneficial, helping to protect us from certain autoimmune diseases and allergies.

Helminths for health?

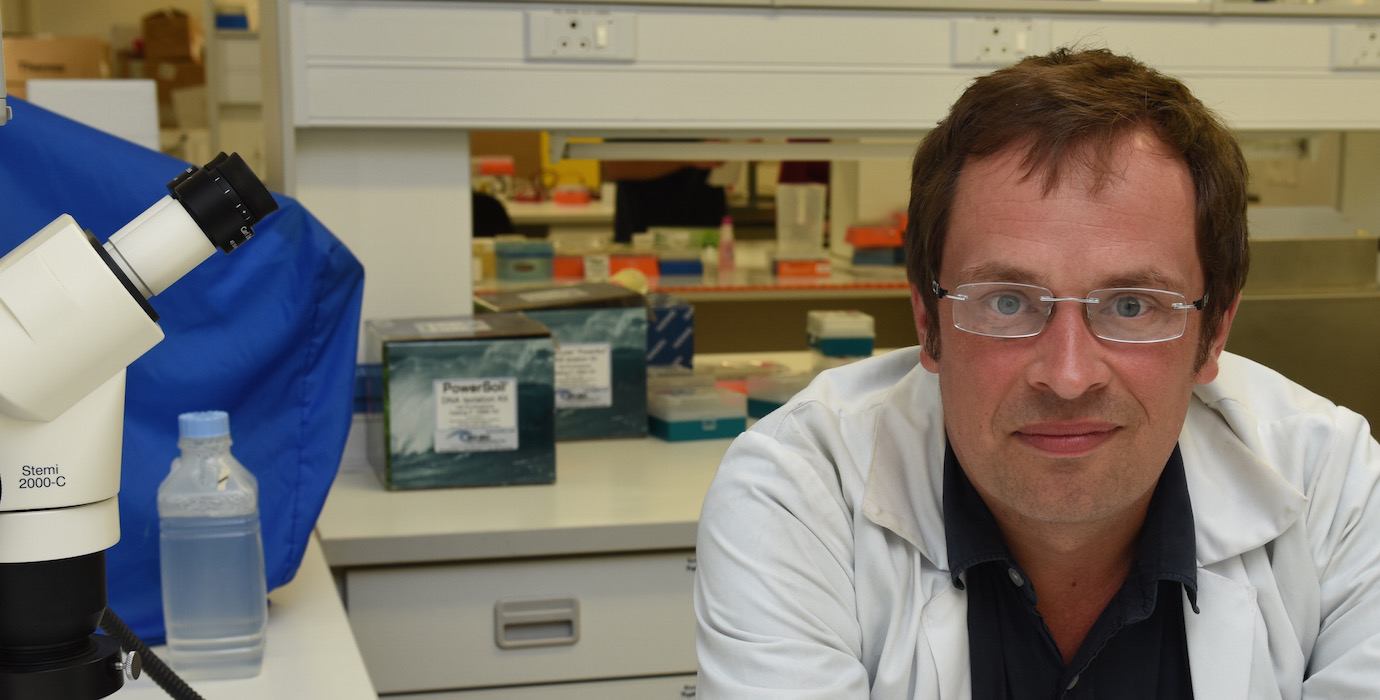

It is this complex relationship between helminths and human health that Associate Professor William Horsnell, a parasitologist at the University of Cape Town (UCT), has been studying for more than a decade. Together with his team at the Institute for Infectious Diseases and Molecular Medicine (IDM) at UCT, he is one of a number of researchers around the world confirming that helminth infections may sometimes be more a help than a hindrance.

“What we see,” he says, “is that in some cases helminths can be bad for our health, but in many other ways, helminths may provide protection or reduce the chances of developing autoimmune disorders like inflammatory bowel disease, multiple sclerosis and diabetes.”

The idea that parasitic worms have co-evolved with humankind to the point that they play a role in regulating our immune systems may sound novel but in fact this field of research has been studied for decades. The first significant demonstration of such a relationship was published in the 1990s from research conducted in Gabon by Maria Yazdanbakhsh which showed that children with helminth infections had a reduced reactivity to house dust mite allergy. A range of studies around the world have since supported these findings.

How exactly do helminths affect our immune systems?

Horsnell’s response to the question of how helminths achieve this regulation, however, is to smile and admit that much about these processes still remains unknown. “It’s important to remember that worm infections can make us ill but the majority of the time they don’t, because the worms want to live within us, not kill us,” he says, “So while we mount an immune response to them, they also regulate this process through secreting copies of components of our immune system such as TGF Beta, a protein well known for its ability to control our immune system.”

One of the reasons that Horsnell finds this field of study so fascinating is the fact that these organisms affect our health in a myriad of ways. For proof, look no further than the variety of research Horsnell and his colleagues are currently engaged in.

Helminths and lung health

Could exposure to helminth infection help ward off conditions such as asthma?

Horsnell, together with Professor Cecile Svanes from the University of Bergen and Professor John Holloway at the University of Southampton, are currently leading the Helminths and allergy in South Africa and Northern Europe project,funded by the Worldwide Universities Network (WUN). This study is looking at the role that parasite infections play in lung health and allergies in Europe, Australia and Africa .

“We assume people in Europe no longer get a lot of helminth infections, which is probably true. But they may get more than we think, especially if they are living on a farm or have pets. Hopefully, this large-scale study will help to answer whether exposure to helminths still occurs in developed regions like Europe and how it may contribute to risk of allergic disease,” Horsnell explains.

In addition, Horsnell, in collaboration with colleagues from the University of Liege, Belgium and Imperial College in the United Kingdom, is exploring whether components of helminths can be used to help prevent and aid in the recovery of respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), a lung disease that is the leading cause for early-life hospitalisation. “There are no reliable therapies, and those available are prohibitively expensive and only effective in certain groups of patients,” Horsnell explains. “RSV often leads to serious respiratory complications that last for years. We’re looking at how components of helminths or controlled infections alter the environment of the lung so that it is primed to rapidly control an infection such as RSV.”

Helminths: a cause for optimism?

Horsnell is careful to point out that in general helminth infections should not be considered a good thing. “In developed countries there is now less exposure to these infections and losing this exposure might have negative effects for public health whereas in sub-Saharan Africa exposure to these infections is very common and can make you very ill; we need to still treat such infections as a problem.”

“No one is suggesting that you should seek out a parasitic worm infection but it does appear that in those places with less helminth infection, diseases like diabetes and allergies have become more common,” Horsnell says. “Right now there is a lot of attention being given to the microbiome (symbiotic or ‘friendly’ bacteria) but we are finding that the macrobiome (symbiotic or ‘friendly’ worms), of which helminths form a significant part when it comes to us humans, are also very important. It is exciting to think that we could use components of helminths or controlled infection to treat some of the most important diseases that we face today.”

There is much more still to be discovered about the role that parasitic worms play in human health but, as Horsnell and other researchers’ work is proving, parasitic worms, far from being an enemy of our health, might yet turn out to be our allies.